No, really.

Hedwig “Hedy” Kiesler is best known for a long career as an actress in Hollywood’s Golden Age, going by the stage name Hedy Lamarr, and having appeared alongside the likes of Clark Gable and Judy Garland in films throughout the 1940s. At the time she was marketed as the “world’s most beautiful woman” by her talent scout. As far as I’m concerned, being an actor in Hollywood’s Golden Age counts as having an interesting life, but for Lamarr, it counts among the less interesting parts of her career.

Her background merits a brief mention before I get to the science. She was born to a Jewish family in Austria in 1914, but raised Catholic. At 19 years old she married a wealthy Austrian arms merchant, Friedrich Mandl, who was also an ardent fascist. She would later describe him as being very controlling, and it’s likely she was being generous with that description, given that she engineered an escape to Paris in 1937 to be free of him. From Paris, she moved on to Hollywood, where she began her aforementioned film career.

She had been interested in science since she was a child, and her interest grew when she was married to Mandl, who would take her to business meetings, which often involved military science. At the height of her acting career, during the war, she tinkered with a few inventions. She followed through on one of them, which ended up being important in the history of radio technology. Her invention was called Frequency-Hopping Spread Spectrum (FHSS) technology.

Technically she wasn’t the first to come up with the idea, but (as far as I can tell) it was her version of it which ended up in US Navy ships and submarines. That didn’t happen until the 1960s, however (after the patent expired). Despite patenting the invention in 1942, the Navy was a bit slow to respond. It was of vital importance to their ships by the Cuban Missile Crisis, though. An updated version of this technology exists in several civilian applications to this day, including GPS, Bluetooth, and Wi-Fi.

What the technology actually does is provide a way to transmit radio signals without fear of deliberate jamming by enemy forces. Lamarr had radio-controlled torpedoes in mind when she worked on it. Had her ideas been implemented during the war, it would’ve been well, pretty useful, I suppose.

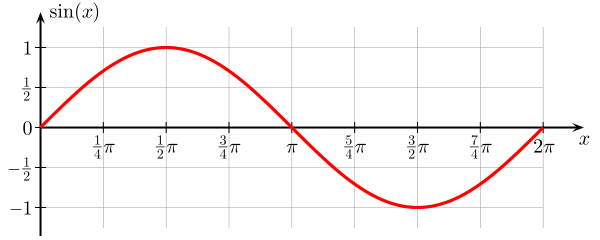

So, radio waves are sinusoids, or sine waves:

They are oscillating excitations in electromagnetic fields, which radio transmitters can generate, and receivers can detect. Signals can be encoded in these oscillations in clever ways I won’t get into here. These oscillations/sine waves have a frequency associated with them. which is just how many oscillations happen per second. This is measured in Hertz (Hz). BBC Radio 1, for example, transmits at a frequency of about 98 MHz, or 98 million oscillations per second. All radio signals are transmitted and received at a certain frequency (technically in a small range of frequencies). This is the number you dial your radio to to receive a signal. (98 FM in the BBC case. FM is a description of how the information is encoded in the radio signal.)

The “frequency-hopping” part of the name of Lamarr’s invention comes from the fact that the radio transmitter (pseudo-)randomises which frequency it transmits its signal at, in a way pre-determined such that the target always knows which frequency to receive signals from. So, many times a second, the frequency you’re transmitting at will change. This is useful because if you’re transmitting at a certain frequency, that signal can be jammed by someone else with a strong radio transmitter transmitting at that frequency. You could overcome this by just blasting the same signal louder, or over a larger range, but both of these are expensive to do.

What FHSS means, as far as potential jammers are concerned, is that you are transmitting over a very wide range of frequencies. This means if someone wants to jam the signal, but doesn’t know the sequence of frequencies the source and target have agreed on, then they need to jam a very large range of frequencies in order to stop the signal. You, however only need to transmit over one frequency at a given time.

She didn’t contribute much to the scientific community, but what she did contribute was forgotten for a long time. It was only in the 1980s that her achievements were recognised, and in 1997 she received the Electronic Frontier Foundation Pioneer Award, along with her co-inventor George Antheil. She died three years later.

I suppose I should end with some sort of “don’t judge a book by its cover” spiel. Yes, she was amazingly beautiful, and yes, clearly she was a talented intellectual, so all of those lessons apply. She’s not even the only actress I know of with a scientific side: Natalie Portman isn’t just Queen of Naboo, she’s a published author in a Neurology journal. (Erdős number of 5!) But the more interesting side of Hedy Lamarr’s story, for me, is how she escaped a clearly abusive relationship, not to mention impending Nazi occupation, and built a better life for herself. And that life happened to include science, technology, and invention, alongside stardom.